We are writing this article to share our strategies, experiences, and lessons that we learned from organizing virtual sessions for the 2020 SIAM conference on the Mathematics of Data Science (MDS20). There were initial tentative plans to move the conference to 2021, but HZB and MAP decided to “go rogue” and instead move their original session online. They organized a two-part minisymposium (which included MF, YHK, and AV among the speakers) on its originally scheduled date (5 May 2020), with the first session from 9:00–10:55 a.m. in Pacific Daylight Time (PDT) and the second session from 12:00–1:25 p.m. in PDT. The 7 talks in their minisymposium were from 7 of the 8 original speakers. After HZB and MAP reached out to their speakers early on to gauge interest in holding an online minisymposium, YC and AV also decided to transition their MDS20 session online. (A while later, SIAM orchestrated many other MDS20 minisymposia and its plenary sessions to move to an online format, and a new MDS conference is slated for 2022.) They held their one-session minisymposium, with 4 of the original 8 speakers, from 9:00–11:00 a.m. in PDT on 4 May 2020, the day before its originally scheduled date. The titles and abstracts for their session are available at https://meetings.siam.org/sess/dsp_programsess.cfm?SESSIONCODE=67901.

If you would like to take a look at presentations fromMDS20 conference, videos of selected talks — as well as from tutorials, plenary talks, and other minisymposia— are available from the Virtual Talk Schedule at the main MDS20 conference website, and SIAM is in the process of uploading these resources to the conference’s YouTube channel.

The registration for HZB and MAP’s session filled up quickly, with 300 participants (the maximum that they could accommodate on Zoom) from all over the world. On the day of their minisymposium, the attendance varied over the day, with as many as about 140 people for some talks. YC and AV’s session had roughly 115 registrants worldwide. Their session’s most-attended talk had about 50 participants. Based on our experiences (although our sample size is small), future organizers of online minisymposia can perhaps expect a maximum of about 40–50% of their registrants to attend at any one time.

To prepare for organizing our online sessions, we learned main ideas from a webinar that was run by Vitomir Kovanovic and Maren Scheffel [1]. In March 2020, Kovanovic and Scheffel transitioned a large, 500-person conference on learning analytics (LAK20) to a virtual setting within 2 weeks after it was cancelled. On 27 April 2020, they hosted a webinar to share their experiences and give advice for organizing online conferences. Some of the tips from Kovanovic and Scheffel were more appropriate for full conferences, rather than minisymposia, but we found their webinar to be very useful and implemented several of their ideas in our sessions. We will highlight them throughout our article.

In the rest of our article, we will discuss our preparation for each session one month and one week in advance of our minisymposia. We will then describe the day of the minisymposia from the perspective of both organizers and speakers. We will conclude with some reflections about our experiences.

1. Two–Four Weeks in Advance of the Minisymposia

Platform and Registration

We chose to host our sessions on Zoom because we had access through our institution. (We did not have a Zoom Webinar membership, so we used the regular version of Zoom.) We initially had people register through Google Forms that we created, as we were working with a Zoom limit of 300 people and we wanted to give out the Zoom coordinates only to people who were planning to attend. We asked people to input their name, institution, and e-mail address. A benefit of the Google-Form format is that this information is collected automatically into a spreadsheet, providing an easy mailing list for subsequent communication.

HZB and MAP’s session: Once we reached our 300-person limit, we closed responses on the form and added a comment that the session was full. Some people contacted us directly about this situation, and we then added them to a waiting list. Once we asked people to register for the session via Zoom (see Section 2), we saw that several people in our original list of people did not ultimately register. We then extended invitations to people on our waiting list.

YC and AV’s session: Because we did not reach capacity in our registration form, we kept the form open and continued to monitor it for new registrants throughout our session. We had several last-minute registrations. One thing that we noticed after our session was that we could have set up our Google Form so that registrants received an e-mail receipt. For future sessions, we recommend setting up a receipt for registrants to be notified that they are (1) successfully registered and (2) will automatically receive the Zoom coordinates by e-mail at a later date, as we received a few questions in the week before our session from people who were wondering if their registration was unsuccessful because they had not yet received the Zoom link.

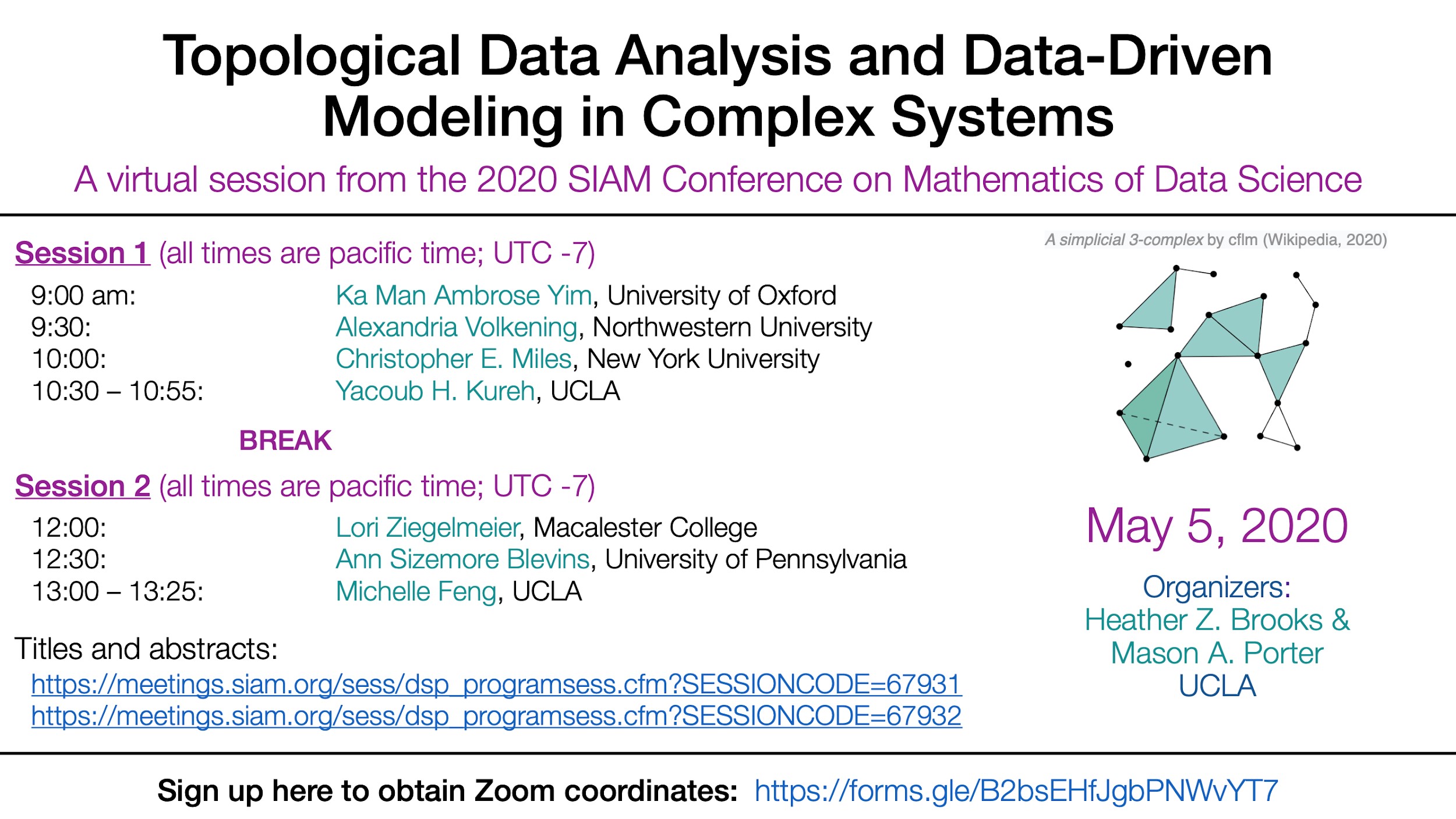

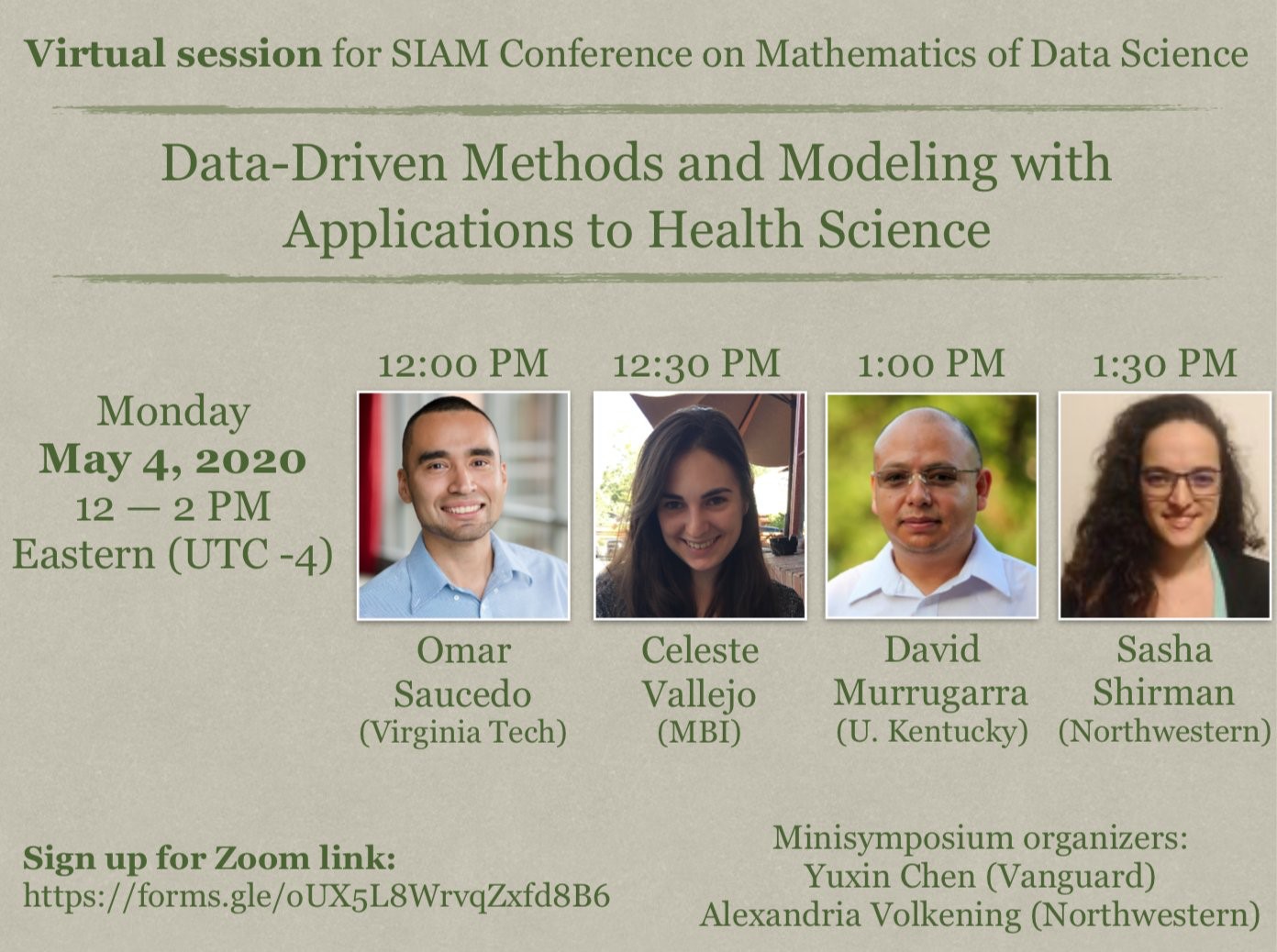

Figure 1. We posted advertisements for our sessions on Twitter in the weeks leading up to our online minisymposia.

Advertising

HZB and MAP’s session: We advertised our session on Twitter (see the Twitter thread at https://twitter.com/masonporter/status/1251594612549906432), on Facebook, through several SIAM mailing lists, and directly to MAP’s research group and UCLA’s networks journal club. We show our electronic ‘flyer’ for our session in the left panel of Figure 1. The specific SIAM mailing lists that we used were those for network science, dynamical systems, and the life sciences. Perhaps because we advertised so broadly, we hit the 300-person cap much faster than we were expecting (in about 2 days, with the initial tweet on a Saturday). There were people who would have liked to register, but for whom there wasn’t enough space.

YC and AV’s session: Following HZB and MAP’s example, we also advertised through Twitter (see https://twitter.com/al_volkening/status/1252337022292770823), as well as through the SIAM mailing list for the activity group on the life sciences, various mailing lists at Northwestern University, and a few research groups. We show our flyer in the right panel of Figure 1. In the future, we recommend sharing the announcement with more SIAM mailing lists to generate a larger attendance. Sessions can also be announced on the online list of free colloquia and talks that is hosted through the American Mathematical Society website.

In the future, one may wish to consider whether to advertise to the SIAM lists slightly in advance of widely spread, publicly available platforms like Twitter. It can take a day or two to get a message approved for some of the SIAM lists. For HZB and MAP’s minisymposium, registration had almost completely filled up by the time it finally went out to the life-sciences mailing list. However, Twitter advertising reaches a broader audience, and it's important to cast a wide net to catch people who otherwise would not be aware of these sessions. In MDS20 sessions that were held after ours (e.g., one organized by Maria-Veronica Ciocanel and Wasiur Khuda Bukhsh), advertisements on LinkedIn were another successful venue for reaching broad groups of people. One of the major advantages of online minisymposia is the opportunity to share sessions with more people.

2. One Week in Advance of the Minisymposia

Instructions for the Speakers

In the week before our sessions, we e-mailed the speakers with a reminder, as well as our instructions and plans for the day. (See Section 3 for these details.) We also asked for permission from each of our speakers to record their talks, and we requested that they send us a copy of their slides (in case any technical issues arose with sharing screens during a session [1]). Following the advice in [1], we offered to do practice Zoom calls with anyone who wanted to practice ahead of time, but we found that all of our speakers were already comfortable with Zoom.

Reminders for the Attendees

HZB and MAP’s session: One week before our minisymposium, we sent out an e-mail to our mailing list to ask people to register via Zoom. One can set up this kind of registration mechanism in Zoom, so that one sends a registration link and then people are automatically sent Zoom coordinates when they register. At this point, we realized that we probably could have just used this approach (advertising with the Zoom registration link) and skipped the Google-Form step. However, we had a very good turnout for our minisymposium, so apparently this small amount of redundancy didn't hurt us too much. We sent one additional e-mail reminder the evening before our minisymposium.

YC and AV’s session: The day before our session, we sent out the Zoom coordinates directly to everybody who had registered in our Google Form. We did not require participants to register again for the Zoom session, so our Zoom link was not tied to specific e-mail addresses. However, we did include a password. We sent out the Zoom information the day before our minisymposium so that this e-mail could also function as a reminder to registrants.

3. The Day of the Session: Organizers’ Perspectives

Speakers

We had the speakers sign in 20–30 minutes before the session in which they spoke so that they could test their slides. We also made them all co-hosts to enable them to share their screens. This ensured that we were able to transition smoothly between speakers. Following the advice in [1], we let our speakers know that we would give them a 5-minute warning as a private message through the Zoom chat window. We suggested that our speakers open the chat window after sharing their screen so that they would be able to easily view this alert.

Moderation

We assigned one organizer to be a question moderator and one organizer to be a Zoom-room moderator. We rotated the two moderator duties between the organizers, although the two minisymposia used different approaches: HZB and MAP swapped after each talk, whereas YC and AV split their session in half. The question moderator introduced the speaker, kept track of the questions in the chat, gave a 5-minute warning to the speaker (via a private message), and prepared questions to ask the speaker if necessary. The Zoom-room moderator was in charge of making sure that there were no disruptions or technical issues in the Zoom session. In practice, the only thing that was necessary for this moderator was to mute participants (and once to turn off a frozen video feed that was distracting) to make sure that there was no background noise. If someone chooses to use a waiting room, the Zoom-room moderator can also be in charge of managing entry into the room.

HZB and MAP’s session: Initially, we suggested that people used the “Raise Hand” feature in Zoom to ask questions, but we found that most people preferred to ask questions by typing them into the chat window. We encouraged our participants to alert us if they had a question, and then a moderator would call on them to unmute and ask their questions. In a few cases, participants requested that the moderators ask their question for them, which is good for accessibility when using a microphone or unmuting is not an option (or if there is any other reason why a questioner prefers it). Based on our experience, we suggest that organizers allow flexibility for the questions and multiple avenues for participant engagement.

We set up the chat so that people could chat only with the hosts. Depending on the expected size of a session, minisymposium organizers may find it desirable to allow full chat functionality for further engagement among audience members. Other types of Zoom rooms allow separate chat and Q & A features. For example, the Zoom webinar platform provides additional functionality that allows participants to upvote questions that arrive through the Q & A feature; this upvoting option can be especially useful for large sessions [1].

YC and AV’s session: We decided to handle all questions through the chat window, and we took care of reading these to our speakers. At the beginning of our minisymposium session, we adjusted the Zoom settings so that (1) only co-hosts could share their screen and (2) our participants, who were already set up to enter the Zoom room with their microphone muted, were not allowed to unmute themselves. To help encourage interactions, we started our minisymposium by asking the audience to type the city from which they were joining in the chat window. (We got this idea from [1].) In an effort to limit the number of chat alerts that our speakers would see once the session started (because we used the chat window to give a 5-minute warning to speakers), we asked participants to direct-message their questions to us, but we continued to keep the chat functionality open to everyone. As questions came in, we collected the questions in a joint Slack channel, so that we could share them with each other and have them readily available after each talk. Having a means of quickly communicating between organizers outside of the Zoom call (in case of technical difficulties or other questions) was one of the recommendations from [1].

Recordings

As we mentioned in Section 2, in the week before our minisymposia, we e-mailed our speakers to ask for their permission to record their talks. For HZB and MAP’s minisymposium, all of the speakers gave their permission to be recorded; for YC and AV’s minisymposium, one speaker elected to be recorded. For each speaker that gave us permission, we recorded their talk separately using the functionality in Zoom. Once we received permission to also post the talks and slides, we submitted them to the session spreadsheet on the main MDS20 conference website (see “Virtual Talk Schedule”) that SIAM set up. MAP and HZB also posted the talks from their session on MAP’s YouTube channel. People asked us about live streaming (which the MDS20 organizers did for most of the conference’s plenary talks, which occurred on later dates), but we did not want to deal with it. However, it is something that minisymposium organizers can consider if they're up for it.

4. The Day of the Session: Speakers’ Perspectives

AV’s perspective: After speaking in HZB and MAP’s session, I realized that my favorite part was receiving questions directly from audience members (especially when they turned their video on to ask a question). I also appreciated that HZB and MAP kept their videos on during my talk, so that I could see a small audience. I think one thing that was missing from both HZB and MAP’s minisymposium and from my minisymposium with YC was the casual interactions that occur after an in-person session. Adding a 15-minute community discussion or coffee break after the last talk may be a beneficial feature for future virtual minisymposia, and I’ve attended some recent workshops where this worked well. In general, I think it’s tougher to create community in online conferences and minisymposia, and we’ve included some resources with ideas for how to do this in Section 6.

MF’s perspective: Like AV, I appreciated the small video audience that I could see during my talk. It was very strange to not get auditory feedback from other people, but it was helpful to at least have a few faces in the audience, even without sound. I really liked the system for moderating questions that HZB and MAP set up. With large Zoom audiences, it can be really difficult to see when people raise their hands or type something in the chat window, and it was very helpful to know that HZB and MAP were keeping track of it so that I didn’t have to worry about missing questions. I love AV’s idea of adding a virtual coffee break after the last talk for attendees to chat. I’ve been to a few (non-mathematical) online seminars with breakout sessions or coffee breaks after the sessions, and I have found it especially nice to be able to talk to fellow audience members.

YK’s perspective: Speaking at HZB and MAP’s virtual session was a really enjoyable experience. Like AV, I thought that the question-and-answer format was done very well. I felt like I was able to have a brief intimate conversation with those who were interested in details that I left out, but it was still shared with everyone. Echoing MF, although you can’t get the full sensory experience when presenting (or lecturing) over Zoom versus in person, it was helpful to have a `grid’ view of several audience members who had their cameras on. Additionally, I used two monitors, so that I could have my presentation on one and the audience on the other. Seeing the organizers (MAP and HZB) front and center was also a nice touch. Having some questions come in live from the chat if they are minor clarification questions can be very useful, while saving bigger questions for the question-and-answer session worked well. I also strongly endorse AV’s idea of adding virtual coffee breaks.

5. Conclusions and Reflections

We found organizing and speaking in virtual minisymposia for the 2020 SIAM Mathematics of Data Science conference to be a rewarding and valuable experience. We were especially pleased with how widely we were able to recruit audience members for our sessions; this, in turn, allowed us to share the work of our speakers much more widely. This type of exposure can be especially beneficial for early-career presenters, of whom we had several. This was a major motivation for our desire for “the show to go on” with our minisymposia.The online format also provided flexibility for presenters and audience members who may not otherwise have been able to attend the minisymposia (e.g., for scheduling, travel, financial, or family reasons). With many of the talks in our minisymposia available on YouTube and on SIAM’s MDS website, people who couldn’t attend the sessions when they were live are also able to watch the talks.

6. Additional Resources

[1] Maren Scheffel and Vitomir Kovanovic. “SoLAR Webinar - Running an Online Conference: Insights from LAK20”, 27 April 2020. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JzLcotqt7B4.

In this webinar, Scheffel and Kovanovic shared their advice and experiences after transitioning a large (500-person) conference on learning analytics to an online format within two weeks after it was decided not to hold it in person. In addition to including useful advice on virtual poster sessions, social events, and other logistics, the webinar itself was a great example of engaging an audience over Zoom. For example, the two organizers swapped who was speaking every 5 minutes or so, using the same set of slides, to keep the audience alert. They also used the chat window to check in occasionally on participants and address some questions that had arisen during the session. In our minisymposia, we implemented their idea of using the chat window to give speakers a 5-minute warning.

[2] Hugo Camargo, Michal P. Heller, Ro Jefferson, Johannes Knaute, Ignacio Reyes, Sukhbinder Singh, Viktor Svensson. “On the efficacy of virtual seminars”, arXiv:2004.09922. Available at https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.09922.

[3] Gretchen McCulloch (@GretchenAMcC) and others who contributed to a Twitter thread on establishing better virtual “hallways” in online conferences. Available at https://twitter.com/GretchenAMcC/status/1282017877013430272.