This obituary will be published in the August 2010 issue of 'Mathematics Today',

the IMA's members publication.

Professor Jaroslav Stark, who has died from a brain tumour just short of his 50th birthday, was one of the first mathematicians to obtain a doctorate for research into chaos theory in the UK. He became a key figure in cross-disciplinary research in the UK, pioneering the use of mathematics to study biological systems. Due to his enthusiasm, clever use of images, clarity of thought and crystal clear prose the developmental biologists and immunologists he worked with could quickly grasp the implications of his mathematics. This allowed mathematicians and biologists to generate mathematical models which made it possible to understand complex biological problems. By 2003 Jaroslav had moved to a chair at Imperial College, and in 2007 he became the Director of the Centre for Integrative Systems Biology at Imperial College (CISBIC), attracting major funding to bring together mathematicians and biologists. Throughout his life he continued to do ground-breaking research in mathematics through papers written for mathematicians, whilst also diversifying his interests to use mathematics in imaginative ways in applications.

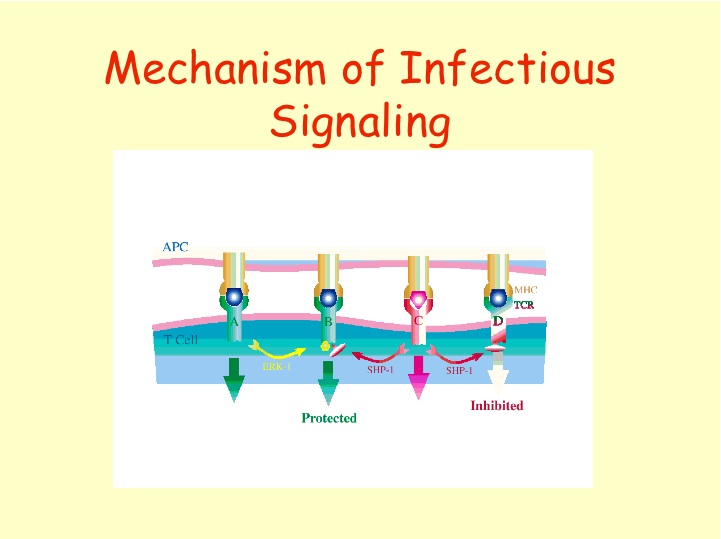

Figure 1 shows an example of the sort of picture Jaroslav could build to put across ideas. It was part of work undertaken with Andrew George, who writes

This figure illustrates work that Jaroslav carried out with Cliburn Chan and myself on understanding the exquisite specificity and sensitivity of the T cell for its antigen, which is such that a T cell can respond to 1-10 agonist peptide MHC complexes against a background of 105-106 irrelevant peptide MHC complexes, yet discriminate between peptides that vary in just a single residue. In work published in PNAS in 2001 we showed that cross talk between T cell receptors could contribute to the specificity and sensitivity. Jaroslav illustrated this in this figure which shows the interaction of a T cell expressing T cell receptors (TCRs, bottom of figure)with an antigen presenting cell (APC, top of figure) that expresses MHC molecules carry different peptides. The scheme shows that a T cell receptor that bound to a ligand for a suboptimal period (labelled C) inhibits (red arrows) the response of adjacent receptors (D), while that which bound for long enough to transmit a signal (A) protects (yellow arrow) surrounding receptors from inhibition (B). The inhibitory effect can improve specificity, while the protective effect can improve sensitivity. The negative signalling was identified by Ron Germain as being mediated by SHP-1, while the protective signal is mediated by ERK-1.

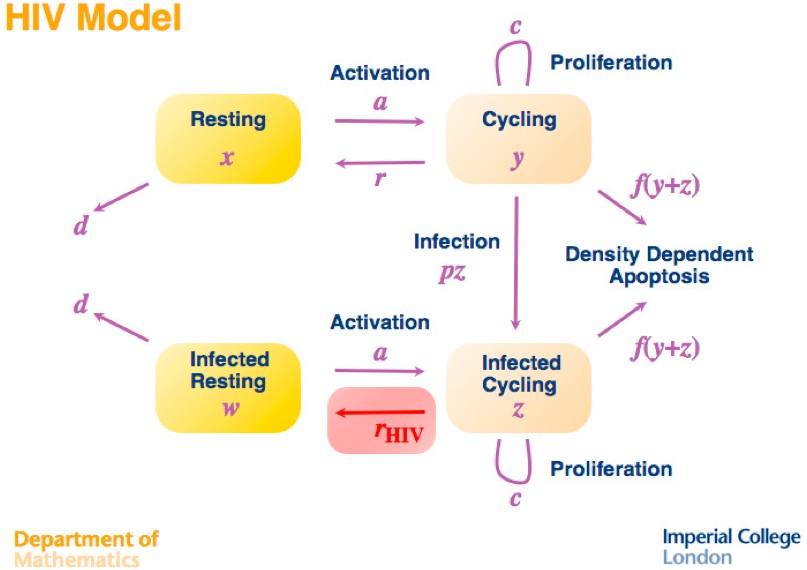

Figure 2 is another example of the visualizations Jaroslav used. In this case it explains a four compartment model of T lymphocyte homeostasis developed with Robin Callard and Andy Yates, showing how HIV infection can alter the dynamics of cell proliferation and death leading to a different steady state with reduced T cell numbers characteristic of HIV AIDS.

Jaroslav was born in Pardubice to the east of Prague in Czechoslovakia in 1960. His mother, Olga, was a paediatrician and his father, also Jaroslav, an eminent paediatric heart surgeon. His family moved to London following the Russian invasion in 1968.

He read mathematics at Peterhouse, Cambridge where he gained a first class degree in 1982 and a year later a distinction at Part III, the Cambridge equivalent of a masters degree (only harder). Jaroslav then moved to the Mathematics Institute in Warwick to undertake graduate research with Sir Christopher Zeeman and Robert Mackay. Robert had just accepted a lectureship there and together with David Rand was making Warwick an international centre for research in applied dynamical systems and chaos theory, building on the expertise in pure dynamical systems that Zeeman had attracted to Warwick. In his thesis Jaroslav proved that a method for proving non-existence of barriers to transport for area-preserving maps was guaranteed to succeed if indeed there were none and sufficient resolution was used, and presented numerics on the boundaries of the chaotic regions. This photo (with thanks to the Mathematics Institute, University of Warwick) shows him in the Coffee Room at the Mathematics Institute with Robert MacKay, David Rand and (I think) Dan Berry.

Here is what Robert MacKay says of having Jaroslav as a PhD student:

Jaroslav was my first PhD student but from the start he was more like a colleague, with great initiative, knowledge and insight. We worked together on filling the gaps in Aubry's theory of minimising orbits of area-preserving maps, which I'd set myself as goal for my first MSc module and I could not have done it without him. He carried out detailed numerical tests of an approximate renormalisation scheme I'd proposed and in particular for boundary circles. When I was stuck on a step to make a non-existence criterion for invariant tori for higher dimensional maps, he instantly said it was trivial and pointed me to a reference. He understood mathematics very fast and could use it to extremely good effect. I shall miss him.

After post-doctoral positions at Warwick and Imperial College Jaroslav spent four years in industry, continuing his research at GEC before returning to academia as a lecturer at UCL in 1993. Here he continued to work with mathematicians and engineers to understand real world implications and applications of chaos, including how to manipulate data to detect chaos. In 1997, the Provost of UCL Sir Derek Roberts asked Jaroslav to set up an interdisciplinary centre at UCL with Robin Callard and Anne Warner. The Centre "CoMPLEX" was established by 1998 and introduced the first interdisciplinary four year PhD training programme crossing the boundaries between the life sciences and the physical sciences and mathematics in the UK. The success of CoMPLEX and the continuing huge success of the PhD programme are a lasting legacy to Jaroslav's enthusiasm and vision. He was made a professor in 1999 and became increasingly involved in research council policy and funding. With another friend, Colin Sparrow, he re-vamped and was joint editor of the journal which is now called

Dynamical Systems.

It was hard to be with Jaroslav without being drawn into a fierce debate. Once, whilst we were working together, Colin Sparrow popped his head round the door to ‘check that we were OK’. Neither of us knew how to respond – we had been so engrossed in our stream of ideas (some good, some bad) that we had not realized that our conversation had become loud enough to convince others that we were about to come to blows.

Jaroslav’s loud enthusiasm went hand in hand with a capacity to engage with people and ideas. His list of collaborators is long, and includes established figures like David Broomhead, Mark Muldoon and Jerry Huke in Manchester. But he also had time to encourage younger researchers, most recently Tobias Oertel-Jaeger at the more mathematical end of his interests, and PhD students and post-docs at CISBIC. He made everyone feel that their opinions were valuable, and was able to extract interesting insights from half-formed ideas as well as encouraging more coherent ideas.

Given this level of engagement at a personal and professional level, it is not surprising that he wrote papers with many of the people he loved best, including his father with whom he published papers on performance monitoring in heart surgery which have become landmarks in this area. He met Kate Hardy, a developmental biologist, at Cambridge and they married in 1987, and it was only a matter of time before he started developing mathematical models to go alongside her biological theory and experiments.

Their collaboration came at an opportune moment. Systems biology, the biology of the twenty-first century which brings a quantitative mathematical approach to the description of biochemical processes, was in its infancy, and Jaroslav and Kate were ideally placed to use their respective expertises to increase our understanding of the processes at the heart of developmental biology. They started with models of ovulation – a fascinating story of how many eggs mature but only one is released at ovulation, and how this mechanism can be disturbed as a result of age or common hormone disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome. This melding of biological experiment and mathematical modelling quickly gathered pace, drawing in scientists such as Robert Winston, whilst the specific problem of ovulation became a recurrent theme and attracted both research council funding and other collaborators such as the clinician Professor Stephen Franks.

Jaroslav and Kate’s son, Daniel, was born in 1996 and this introduced a new and rich dimension to his life. Together they enjoyed sharing walks, skiing, photography, music and holidays.

In 2009 he published papers on strange attractors, spatial structure in tissues and organs, and models of red blood cell production and consequences for malaria. This range reflects his broad interests, and the way these interests were mediated through friendships. Throughout his career Jaroslav was involved in the creation of science policy, he was an Associate Fellow of the IMA and served on scientific advisory boards both nationally and internationally. Through this and his own work he has helped to shape the cross-disciplinary landscape of research in this country.

Many of us in the dynamical systems and systems biology community feel the loss of Jaroslav as the personal loss of a friend as well as the loss of a valued colleague at a tragically young age, and I would like to end with some memories and appreciations from four of us; these were written as part of the Appreciation at Jaroslav’s funeral, on what would have been his 50th birthday.

Paul Glendinning (mathematician): I will remember Jaroslav lounging in a chair with a mug of coffee in his hand. He had a slow, drawled ‘yeesss’ which could mean any of three things. Followed by ‘and’ it meant he liked your idea and wanted to follow it with some more acute observations. Followed by a pause it meant he hadn’t decided yet, but would give you a bit more time to expand on your idea. Followed by ‘but’ it meant NO (and he’d always explain why).

David Broomhead (mathematician): I can think of several conferences over the years where I have arrived wondering why on earth I had bothered to come.... and then, on wandering into the bar after registration, being greeted from across the room by a long drawn out "Hello, David" and knowing that whatever happened in the conference there would be some important and interesting discussions in the bar (or in the case of one conference in Maui, on the beach). Several papers with Jaroslav began life in this way, and in one case at least, several papers resulted because he took a comment of mine far more seriously than I did myself, and went away and did a tremendous amount of work before inviting me down to London to discuss where it might go.

Stephen Franks (clinical biologist): Jaroslav made a huge contribution to mathematical biology and I was fortunate to be included in an already productive collaboration between Jaroslav and Kate. Jaroslav brought real insight and an incredible knowledge of biology into trying to understand the wonders of the physiology of the ovary and its clinically important disorders. Our conversations didn't usually start at the bar but quite often finished up in a favourite restaurant.

But the image of Jaroslav that has most occupied my mind in the last few days is of him at his most relaxed. For 2 or 3 years our families took our holidays nearby in France. We would play tennis in the early morning sunshine and then sit having breakfast on the terrace of their apartment. I can picture Jaroslav reading last week's Observer, eulogising about the latest batch of Kate's homemade jam, lingering over a cup of coffee that had long gone cold and looking forward to a pilgrimage to the local pottery fair.

John Elgin (mathematician): In 2001 I was on sabbatical in Rome and was trying to persuade Jaroslav to make the move from UCL to Imperial College. He had spent a couple of years studying 'real' biology and was excited at the possibility of setting up a group to explore applications of maths to real problems in biology. We had several email exchanges, then met in a pub in Ealing, where we both lived - I remember it clearly because I bought the round (painful!!). I made various suggestions, most of which elicited that `yesss' response from Jaroslav, which of course when I knew him better realised meant 'noooo, I don't think so'…Anyway, the happy outcome was him joining us at Imperial in January 2003. The rest is history: he led CISBIC to the prominent place it now enjoys in this research area. So that elongated 'yessss' will have a permanent echo in the department.

Paul Glendinning

Professor Jaroslav Stark, 17 June 1960-6 June 2010

Professor of Applied Mathematics, Imperial College, and

Director, Centre for Integrated Systems Biology at Imperial College (CISBIC)

Published in

Mathematics Today, the IMA’s members magazine, August 2010.